For Equatorial Guinea, the problem is this: If the country hopes to realize its gas potential, it needs more feedstock for its Gas Mega Hub (GMH) at Punta Europa on Bioko Island

Egalement disponible en Français

JOHANNESBURG, South Africa, March 5, 2024/APO Group/ —

By NJ Ayuk, Executive Chairman, African Energy Chamber (https://EnergyChamber.org).

Will Equatorial Guinea fulfill its promise as a gas “mega hub,” or will stalled negotiations turn what should be a national economic boon into a missed opportunity?

The answer depends largely on how quickly the country can nail down gas supply agreements from Nigeria and Cameroon.

Right now, things don’t seem to be moving nearly fast enough.

As the African Energy Chamber’s (AEC) report, “The State of African Energy 2024” suggests, oil and gas project delays are nothing new on the continent, and they have the unfortunate ripple effect of slowing resource monetization and economic growth. Let me be clear, we at the AEC believe in Free markets, limited government, individual liberty, Gas Baby Gas and good old fashion hard work.

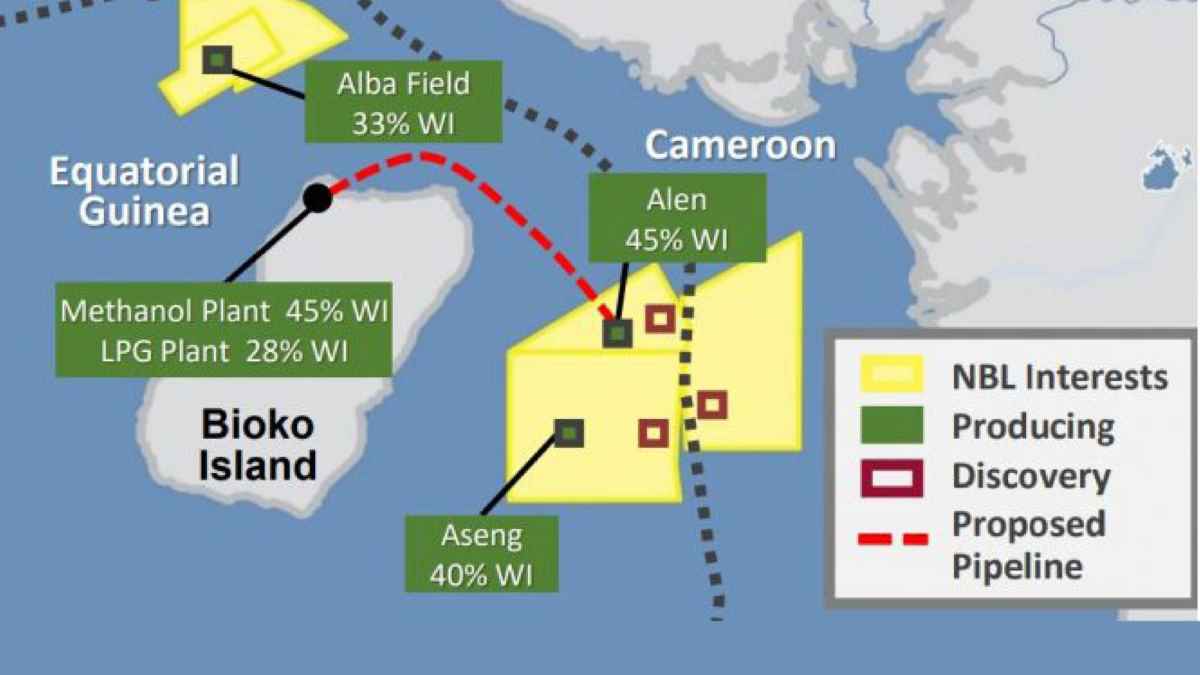

For Equatorial Guinea, the problem is this: If the country hopes to realize its gas potential (the country has more than 1.5 trillion cubic feet, or tcf, of proven natural gas reserves), it needs more feedstock for its Gas Mega Hub (GMH) at Punta Europa on Bioko Island. For more than a decade after the liquefied natural gas (LNG) plant there was commissioned in 2007, the facility depended solely on supplies from the Alba field. Product was acquired under a purchase and sales contract now nearing the end of its 17-year term.

With the Alba in decline, though, operations were in jeopardy. That was until American energy producer Marathon Oil Corp. — the facility’s majority stakeholder — began an expansion project that diversified supply. The first step was to tie in the Gulf of Guinea’s Alen field, which delivered first gas in 2021. The good news continued in 2023, when Marathon announced through its affiliate, Marathon EG Holding Ltd., that it had signed a heads of agreement (HOA) with Equatorial Guinea and Chevron’s Nobel Energy EG Ltd. to continue developing the GMH. (An HOA is a non-binding letter of intent between parties in a potential partnership.) The plan is to continue processing gas from Alba while also bringing gas onshore from the Aseng field.

During the announcement, Marathon executives said the HOA would increase the company’s exposure to global LNG pricing, which would improve both its earnings and cash flow in Equatorial Guinea. For the country, Marathon said, it would further position Punta Europa as a “world-class hub for the monetization of local and regional gas.”

Around the same time, Equatorial Guinea and Cameroon committed to jointly develop and monetize oil and gas projects on the border between the two countries, a historic moment in bilateral cooperation. The agreement was ratified by Equatorial Guinea upper and lower chambers recently.

If it feels like it should all be smooth sailing from here, you’re right: It should be. That’s not the reality, though. While the reinvestment in GMH is a bright spot, the fact is, those LNG plant expansions are years off, and there’s been no other progress in domestic production since 2021. New gas projects need to come in and it might make sense for the government to be pragmatic enough to incentivize new investment so the IOC’s can inject the capital needed. As for the deal between Equatorial Guinea and Cameroon, it looks great on paper, but there needs to be more movement on both Equatorial Guinea and Cameroon. One issue: Cameroon has been focusing on domestic priorities, as has Nigeria, which could supply gas to Equatorial Guinea if it didn’t need most of its production itself. Even the gas Nigeria is willing to move to the GMH has been sidetracked by delayed contract negotiations.

The Minister of Mines and Hydrocarbons, Antonio Oburu Ondo has kept the pace going and shown a lot of pragmatism and drive to get a lot moving on gas. I want to urge the oil and gas companies operating in the country to meet him halfway and close these deals that stand to benefit the people of the country. Equatorial Guinea has been good to the oil and gas industry and the energy sector has an opportunity to bring back the old blues again. Work needs to be done by both sides.

Our recent agreement with Cameroon will see the two countries jointly develop oil and gas projects along our maritime borders

In a recent interview with the African Energy Week, when asked about cross border and in country developments, the Minister stated “In addition to drilling works being undertaken to improve and maintain production levels at existing fields, the Ministry is making great strides towards accelerating exploration across the country’s offshore acreage. Our recent agreement with Cameroon will see the two countries jointly develop oil and gas projects along our maritime borders, including the Yoyo and Yolanda fields, the Etinde gas field and the Camen and Diega fields.

The country’s enabling environment for investment and strong record of successful offshore finds have also seen new E&P players join the market. Earlier this year we also signed three production sharing contracts with Panoro Energy and Africa Oil Corporation. These contracts are expected to further open up the upstream market. Additionally, we have several global energy majors and independents progressing with exploration and are optimistic about these campaigns. The only way to address production declines is to explore, drilling more wells and unlocking the potential of offshore basins.” Well said, we just have to push forward and make it a success.

The Etinde gas field offshore Cameroon best hope for monetisation was with Perenco. However the delays in approvals from Cameroon led them to change strategy with their investments. This could have been a massive opportunity to supply feedstock gas to the EG LNG plant. The regulatory regimes need to address cross border gas deals especially where the geology is complex.

For a while, it seemed like the proposed Golar floating LNG (FLNG) facility would solve many of the GMH’s supply problems, as well as overcoming the difficulties (and enormous expense) associated with pipeline transportation of offshore gas to onshore processing plants. A FLNG facility floats above an offshore gas field and is used to produce, liquefy, and store LNG before it is transferred by ship to onshore processing facilities.

Golar has a successful track record of operating innovative FLNG technology in Africa. In 2018, it completed Africa’s first FLNG, the Golar Hilli, offshore Cameroon. The facility, which produces about 1.4 million tons per year, was also the world’s first FLNG plant created from a converted LNG carrier.

With that background, it was hard to be anything but hopeful when Golar signed a memorandum of understanding (MOU) with Equatorial Guinea to develop a block estimated to hold 2.6 tcf of natural gas. Yet despite the enormous opportunity for the company and the country — especially considering Europe’s continuing quest to replace Russian gas since the conflict in Ukraine began more than a year ago — negotiations are at a standstill. We at the Chamber hope these negotiations can be revitalized or another party is brought into the country to carry on this project.

In this case, being unable to participate in an eager market is just part of the story. This is an economic issue to be sure, but it’s one that can be veiled by the politics of climate change. Here’s what I mean. When asset development is put off, it comes with a very real risk of the underlying gas being considered “stranded.” Climate activists will say the project will never go forward and will push for it to be abandoned. Gas that could be monetized will be lost to the energy transition.

No Shortcuts and Avoid Resource Nationalism

As I alluded to earlier — and as “The State of African Energy 2024 Report” suggests — there’s never been a shortcut to getting African hydrocarbon projects off the ground. I’m not saying that these enormous projects won’t by necessity take time. But national governments have been — and continue to be — a source of unwarranted delays, whether it’s by dragging their feet toward the negotiating table, changing the rules after awarding a project — which makes negotiations go on longer than they should — or making energy companies wait two years or more before sanctioning the exploration projects they propose. When your state revenues rely on oil and gas, why would you actively prevent things from advancing?

Yes, I’ve heard the arguments for resource nationalism. Yes, I know that this is “our” oil and gas. But thinking about this as an us versus them scenario isn’t helping anyone. Having resources isn’t enough; you need the financial ability to do something with those resources. This has been “our” oil and gas for centuries, but we couldn’t marshal the technologies and the financing to go out there and drill a $100 million deepwater well. Yes, of course we should benefit from full-on local content, full-on empowering our people and communities, full-on having the right kinds of profit-sharing, and royalties, and taxes, full-on empowering community, full-on having the right kind of share and full-on having the right kind of taxes. But until we have the ability (and financial wherewithal) to extract our oil and gas like Marathon, Chevron, Golar, and others do, why are we adding roadblocks instead of incentivizing production? Sometimes, I think our governments simply ignore the fact that investors are spending a lot of money to make these projects work and that their successes will be, eventually, our own.

Instead of delays, then, we need to give investors the confidence that we stand with them, and that we’re determined to make projects work. In all my work across Africa, I have always told Presidents and Ministers I have been privileged to earn their trust, that Africa needs pragmatic free market policies to attract capital into Gas markets. One of the reasons Equatorial Guinea was for so long the darling of energy investments was that the government was willing to find solutions. Now, in a more competitive environment, where Equatorial Guinea is jockeying for dollars with Gabon, Cameroon, Namibia, Suriname, and Guyana, the government should be doing everything it can to finalize negotiations and fast-track projects, not sitting back on its heels and waiting for — what? Social spending, among other things, depends on us moving energy projects forward.

Right now, there’s no way of knowing how long it will be before Equatorial Guinea’s GMH fulfills its destiny. But we do know this: Every day without progress means lost revenues.

Distributed by APO Group on behalf of African Energy Chamber.